Rapid weight gain in early life is a well-documented risk factor for childhood obesity, as well as the onset of various cardiometabolic indicators in the paediatric population. The role of rapid weight gain, defined as abnormal weight gain within the first two years of life, on childhood obesity has been extensively explored in high-income countries. However, rapid weight gain has received less attention in middle-income countries despite obesity’s disease burden on their populations. In a recent publication in The Lancet Regional Health – Americas, Carolina Santiago-Vieira and colleagues explored the relationship between rapid weight gain and obesity in one such country, Brazil. Their population-level analysis provided key insights into growth trajectories in a large cohort of children and adolescents, with results suggesting that rapid postnatal weight gain shows a positive correlation with above-average body mass index (BMI) in the paediatric population. GlobalData epidemiologists forecast a slight decrease in the disease burden of paediatric obesity in Brazil, with the diagnosed prevalent cases of obesity declining from over 4.4 million cases to approximately 4.3 million cases between 2025 and 2031. Despite these promising trends, understanding the interplay between weight gain in early life and its downstream impacts on metabolic health is pivotal in curbing the obesity epidemic in Brazil.

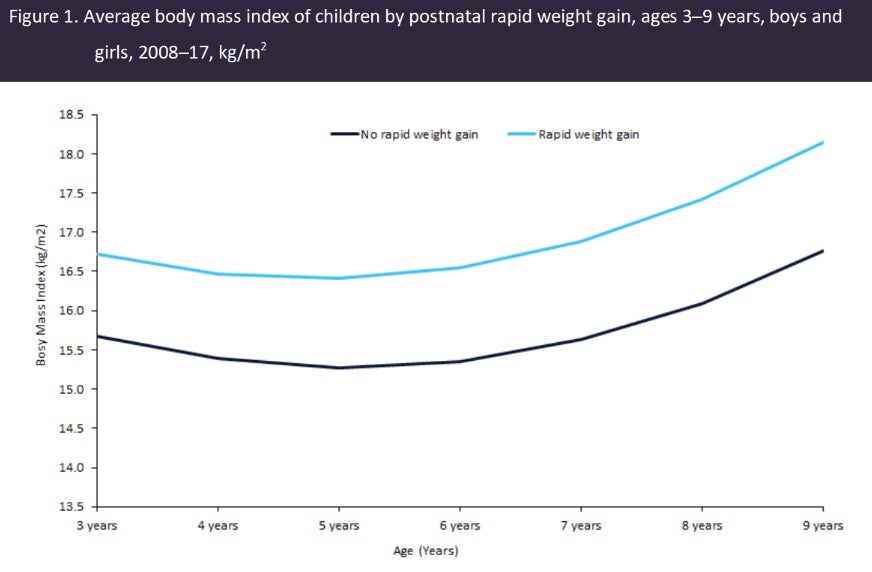

Santiago-Vieira and colleagues performed their analysis using linked data between Brazil’s National Live Births System and the National Food and Nutritional Surveillance System between 2008 and 2017. These sources represented a study cohort of 1.7 million children aged 0-9 years with anthropometric and sociodemographic data. The principal relationship observed by the authors was between birth weight, early rapid weight gain, and BMI over the course of the participants’ first nine years of life. The study results suggested that among children with adequate birth weight, rapid weight gain in the postnatal period was correlated with a higher BMI than those who did not experience early rapid weight gain (Figure 1). The same pattern was observed in the low birth weight and above-average birth weight cohorts across both sexes. Furthermore, BMI tended to slightly decline after aged three years before increasing again at aged five years, especially among children aged 0-2 years who experienced rapid weight gain.

The work produced by Santiago-Vieira and colleagues yields valuable insights into growth patterns in adiposity during early life. By identifying infants undergoing rapid weight gain, healthcare practitioners and caregivers have the opportunity for early intervention into the prevention or mitigation of childhood obesity through the adoption of healthy lifestyle and diet. Moreover, this publication and other supporting works can guide public policy by informing health promotion initiatives. The long-term impact of such efforts can be resounding. Early intervention in the onset of childhood obesity is critical to the prevention of cardiometabolic risk factors later in life.