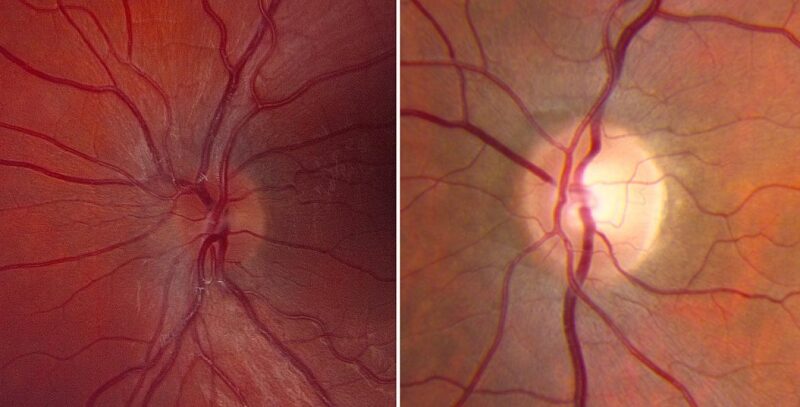

The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) has reported findings from a Phase I clinical trial where a gene therapy was found to be safe but lacked efficacy to treat Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), a degenerative retinal disease.

The gene therapy is intended to restore the ND4 gene’s function by injecting a viral vector (AAV2) that carries a normal gene into the left or right eyes of the patients.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

On injecting the viral vector, it deposits the gene into retinal ganglion cells where it merges into the nuclear DNA of the cell.

Sponsored partly by the NIH unit National Eye Institute, the trial enrolled 28 patients.

In the trial, scientists analysed four therapeutic doses of the gene therapy, each having a different gene vector concentration.

Subsequently, the team observed the trial subjects for up to three years for adverse events, variations in visual function, including acuity, and immune response to the therapy.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAccording to the findings, no substantial safety concerns were observed but the gene therapy failed to improve or decelerate vision loss even at the highest dose.

Inflammatory eye ailment uveitis, which was more common with higher dosages, was the only treatment-related safety concern.

Furthermore, uveitis was reported in 71% of subjects who received the highest dose versus 15% for all other arms combined.

In a press statement NIH said: “Despite the therapy’s good safety profile, investigators were unable to show that it prevented vision loss.

“Some participants’ vision improved in the injected eye, the fellow eye, or both.

“Improvements are known to occur among people with LHON; however, participants with the least affected vision (20/40 or better) at the time of enrolment did not have vision preserved, losing about three lines of visual acuity, as measured on an eye chart, during the first 12 months after injection.”

Trial investigators noted that the gene therapy for LHON could offer visual benefits to some people, but the effect is at best modest.

Based on these data, the investigators will not pursue further phases of clinical testing.

Cell & Gene Therapy coverage on Clinical Trials Arena is supported by Cytiva.

Editorial content is independently produced and follows the highest standards of journalistic integrity. Topic sponsors are not involved in the creation of editorial content.