Doctors at the University of Illinois Hospital have successfully treated seven sickle cell disease patients using stem cells from donors previously thought to be incompatible, a procedure made possible due to a new transplant treatment protocol.

The new protocol allows family members of patients with aggressive sickle cell disease to donate stem cells if half or more of their human leucocyte (HLA) markers match. Previously, donors had to be ‘fully-matched’, meaning they have completely corresponding HLA markers.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

HLA markers are proteins found on the surface of cells, which regulate the immune system by helping identify the cells which do and do not belong in the body. As they are inherited from parents, family members are the most likely donor candidates.

The more closely matched a donor and recipient are, the less likely it is that the patient’s body will reject the donor cells. The problem with sickle cell disease is that only 20% of patients have a family member who is a fully matched donor.

“We have made great strides curing adults with sickle cell disease with stem cell transplants, but the unfortunate truth is that the majority of these patients have, until now, been unable to benefit from this treatment because there are no fully-matched HLA-compatible donors available in their family,” corresponding author Dr Damiano Rondelli said.

By allowing ‘half-matched’ donors, the new protocol needs only small doses of chemotherapy, and will significantly increase the number of potential donors for each patient.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataBetween January 2014 and March 2017, a total of 50 adult sickle cell patients were screened by Rondelli’s team as candidates for a half-matched stem cell transplant. Of these, ten received a transplant. As the initial two transplants were unsuccessful, the doctors adopted the new protocol.

“We modified the transplant protocol by increasing the dose of radiation used before the transplant, and by infusing growth factor-mobilised peripheral blood stem cells instead of bone marrow cells,” Rondelli said.

“These two modifications helped ensure the patient’s body could accept the healthy donor cells.”

Eight patients received the modified transplant, one of whom experienced chronic graft-versus-host disease. The remaining seven patients report a maintained 95% or higher stable engraftment, with improved blood work demonstrated at least 12 months following the procedure.

“These patients are cured of sickle cell disease,” Rondelli said.

“The takeaway message is twofold. First, this transplant protocol may cure many more adult patients with advanced sickle cell disease.

“Second, despite the increasing safety of the transplant protocols and new compatibility of HLA half-matched donors, many sickle cell patients still face barriers to care—of the patients we screened, only 20% underwent a transplant.”

According to Rondelli, around 20% of the lack of access to the trial was due to denial of medical insurance. Other factors included personal decisions and high rates of donor-specific antigens in patients who had received frequent blood transfusions.

Rondelli’s team runs the largest sickle cell programme for adults in Chicago, and is known for its procedure performed around six years ago which used chemotherapy-free fully-matched stem cell transplants for sickle cell patients.

The results of the modified procedure were reported in the journal Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

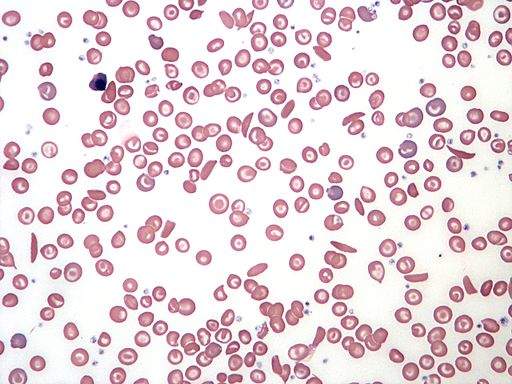

Sickle cell disease denotes a group of inherited conditions which affect the red blood cells, with the most severe form being sickle cell anaemia. The disease causes people to produce malformed red blood cells which can become stuck in blood vessels and often die sooner than healthy blood cells.

Symptoms of the condition such as pain and an increased risk of infection can be treated with ordinary painkillers and daily antibiotics. Severe side effects such as anaemia are currently treated with blood transfusions, while stem cell and bone marrow transplants are seen as the only means of curing the condition, though the risks involved mean they are rarely used.