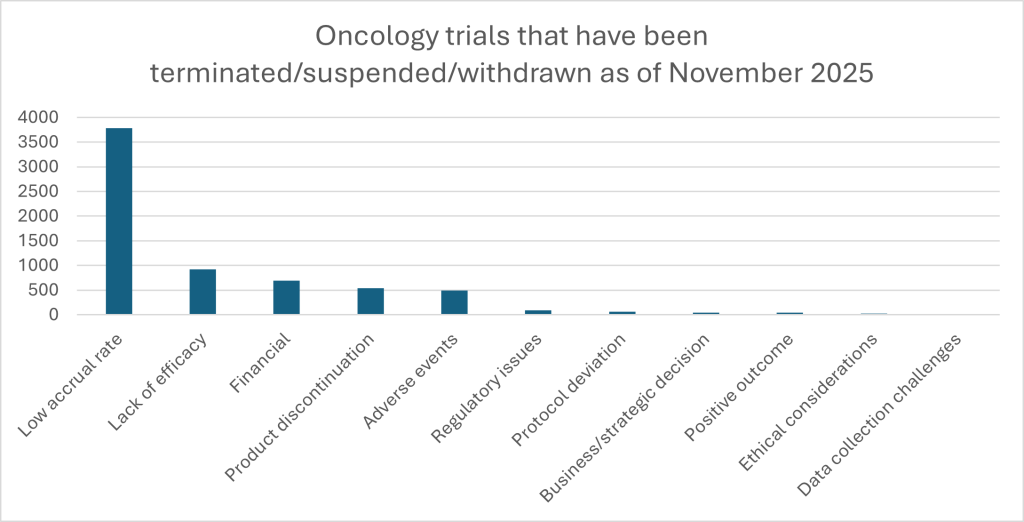

The volume of current activity in the oncology space is enormous. GlobalData’s clinical trial database – a repository of data on trials across the globe from the past two years – contains a total of 113,629 cancer trials as of November 2025. This includes over 9,000 active immuno-oncology trials and nearly 17,000 targeted therapy trials in the oncology space. What we know from the numbers is that this intensity does not translate into speed. Overall, 21,389 – almost one in five – have been suspended, terminated or withdrawn. Low recruitment is the single most cited reason, responsible for 3,784 early endings, or 17.7% of all discontinued oncology trials. Lack of efficacy accounts for 919 and adverse events for 491, equivalent to 4.3% and 2.3% respectively, with financial decisions contributing a further 710 terminations. Operational issues such as protocol deviations, changes in regulatory pathway and data-collection challenges comprise the remaining drivers of trial failure.

It is clearly a mixed picture. For example, for solid-tumor active-control studies, GlobalData’s feasibility modelling estimates an 84.71% likelihood of completion and only a 0.74% chance of suspension.[1] In short, a paradox is evident in the oncology trial data: oncology attracts investment, innovation and regulatory attention despite its trials being slow to activate and vulnerable to outsized recruitment challenges. What are the key trends underpinning this mixed picture, and how can researchers respond?

Oncology’s unique position

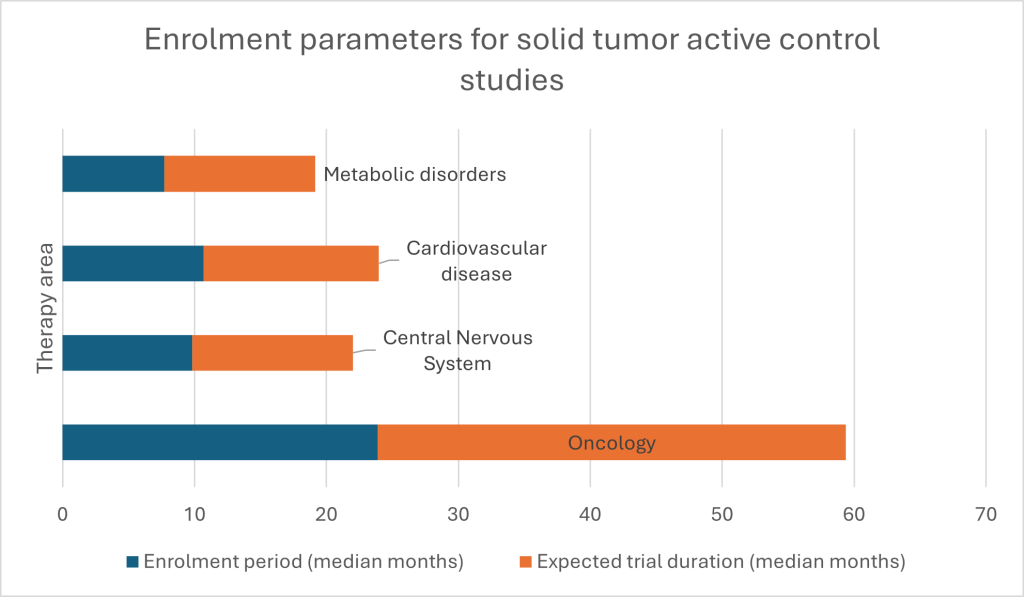

Oncology trials cluster where medicine, biology and logistics are all most demanding. For example, GlobalData’s benchmarking of solid-tumor active-control studies shows a median enrolment period of just over 23 months, and a median total trial duration of nearly 36 months. Impediments include navigating patient welfare, study design – specifically reaching necessary endpoints – and the imperative of reaching adequate numbers, despite only a fraction of patients participating in trials. To put agility at the heart of solid-tumor trials and oncology more widely, new approaches are needed, both in treatments offered and enrolment; only then can issues like modest cohort sizes be addressed.

What does the underlying data say about the key drivers of sluggish oncology trial progress? One driver is related to complexity of protocol design. Another is, when regulators are evaluating against established standard of care marginal gains are not enough. Next, many of the terminated studies may have been technically sound, but outperformed by existing options or were hindered by slow recruitment in crowded indications. For example, one recent study found protocol design was among the top reasons for slow accrual in both phase I and phase II oncology trials.[2]

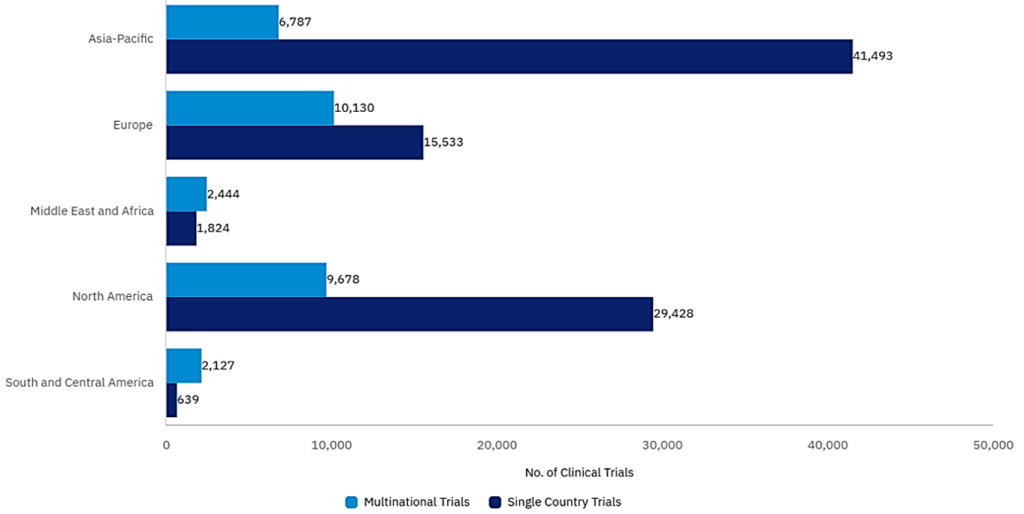

The evolving regulatory environment is another area in need of attention. Although oncology clinical development pathway mirror that of conventional drugs, there is an opportunity for products in high-unmet-need cancers to seek approval based on Phase II data, often under accelerated pathways such as RMAT (Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy Designation)[3] in the US or SAKIGAKE in Japan.[4] These programmes can shorten the distance from first-in-human to regulatory approval. To accomplish this, there is an increased burden on designing the right study, identifying the right targeted patient, using the right comparator, while capturing the most meaningful endpoints throughout the clinical phases of development. Missing any of these can result in adding years of additional work and costs to the drug development journey. Geography, and an increasingly complicated geopolitical environment, compounds efforts to reach key targeted patient populations across oncology indications. With oncology such a mainstay of public health, identifying the right patients for new therapies across geographies is of growing importance. However, the global preference of single country trials in oncology suggests that many sponsors prefer to avoid the complexity of cross-border programmes, provided they can navigate key country regulatory and commercial launch strategies. Additionally, rising tariff barriers and increasingly frosty relations between biopharmaceutical powerhouses in North America, Europe and Asia, are contributing to more caution and slower access to targeted patients in under-served regions.

On top of this, some of the most advanced modalities demand unique and specialist infrastructure. These trials often require tailored surgical procedures, biomarker testing for patient screening, and suitable centres may be limited and heavily subscribed, which slows site identification and qualification. Even in antibody or small-molecule oncology trials, sponsors must contend with specialist diagnostics, intensive safety monitoring and, in many cases, prolonged follow-up obligations.

The hurdles involved in beating the existing standard-of-care is evident in recent immuno-oncology failures. Roche’s SKYSCRAPER-14 trial in first-line hepatocellular carcinoma tested a triplet of tiragolumab, atezolizumab and bevacizumab against an established regimen. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was practically indistinguishable – 8.3 months in the triplet arm and 8.2 months in the control arm. This suggests that, while the study passed regulatory muster, the study failed to have a clinically meaningful or useful endpoint. Earlier TIGIT-targeted studies have met similar fates.

This presents researchers with a challenge. In a 2025 GlobalData survey of high-prescribing immuno-oncology clinicians, 27% cited the immunosuppressive tumor micro-environment as the most challenging aspect of optimising immuno-oncology therapy, 21% pointed to tumor heterogeneity and 15% to low tumor immunogenicity. These same features drive intricate inclusion and exclusion criteria, complicated stratification and long follow-up periods. All of this means slower trial start-ups, dampened enrolment and missed primary endpoints If the right targeted patients are not identified and accessed.

Traversing the hurdles

An evolving regulatory environment, geopolitical obstacles, increasing protocol design complexity – what can oncology sponsors do? Given these pressures, many oncology sponsors turn to contract research organisations with clinical development expertise, deep therapeutic knowledge, an ability to design and support adaptive and novel trial designs, and geographic reach.

If, as GlobalData figures suggest, a well-designed and planned oncology tumor active-control study has an 84.71% chance of completion, and low accrual is the leading cause of study failure in oncology clinical development, leveraging a CROs who can close the gap is crucial for success. For example, Caidya, the leading oncology CRO, emphasises “quality treatment centres” that combine scientific and clinical understanding with the operational infrastructure and proximity to patients to increase the opportunity for success of cutting-edge therapies.

Caidya’s clinical operations teams are trained to interrogate and identify solutions for site capacity, competing studies and likely bottlenecks rather than rely on optimistic self-reporting. So, utilizing their expertise is beneficial for every phase of clinical study.

The results of Caidya’s approach are clear. The company reports trial activation-to-close times around 60% faster than the industry average, supported by a global oncology delivery footprint across more than 50 countries and regions, with differentiated strengths in North America and the often hard-to-reach Asia-Pacific region. Its integrated medical, scientific and operational teams engage early in programme design. 97% of its project managers have oncology experience, with nearly 30% also grounded in hematology.

For sponsors, the calculation is clear. Choosing clinical sites on name recognition alone or spreading trials thinly across regions without real insight into regulatory and targeted patient population, is an expensive gamble. Partnering with a CRO who has a proven track record in oncology and has a deep understanding of the targeted patient population and patient journey will de-risk your drug development program.

Complexity in oncology trials is never avoidable, but the worst delays and failures are. A rigorous approach to feasibility, a globally aware site strategy and early collaboration with experienced partners can shorten activation timelines, protect studies from recruitment collapse and bring much-needed therapies to patients more quickly. Researchers who want to turbocharge their oncology productivity should act now. Fill in your details on this page to learn more.

Caidya is the trade name of dMedClinical Co. Ltd. and its global holdings. Clinipace, Inc. is one company in the Caidya group of companies. In 2021, Clinipace, Inc. was acquired by dMedClinical Co. Ltd., a privately held company, whose investors include entities located in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and which may be subject to PRC laws and regulations that differ from those of the United States.

[1] GlobalData report, “Clinical Trials: Comparator Study Trends,” 2025.

[2] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8573122/

[3] https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/regenerative-medicine-advanced-therapy-designation

[4] https://www.pmda.go.jp/english/review-services/reviews/advanced-efforts/0001.html