Over the history of clinical research, patients have cited many reasons for withdrawing their participation from a clinical trial. While some reasons are difficult to avoid, such as unforeseen logistical challenges or harmful side effects, many others are strongly related to the burden of site visits, which can be uncomfortable, stressful, and time-consuming for patients.

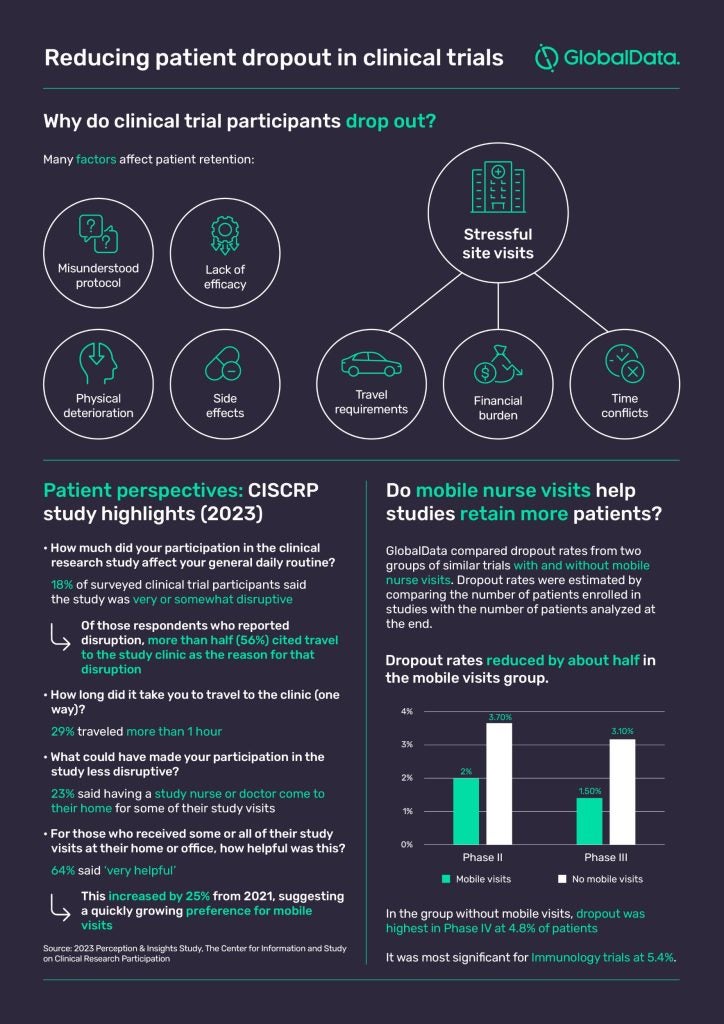

In 2023, 29% of clinical trial participants surveyed by CISCRP said they had to travel more than an hour (one-way) to the study clinic. Moreover, 18% of participants said the study they partook in was ‘very’ or ‘somewhat disruptive’ to their daily routine, with more than half attributing this to travel requirements.

Expenses are not always reimbursed and visit schedules can be inflexible. Considering the longitudinal nature of some trials, it is no wonder the constant cadence of site visits can take a physical, emotional, and potentially financial toll on participants.

Now consider that certain types of patients may experience the burden of a trial differently, and that’s where attrition bias develops. Attrition occurs when patients decide to drop out of a clinical study, and bias comes into play when the participants who leave the study differ in specific (and potentially research-skewing) ways from those who remain.

How decentralized clinical trials address these challenges

Many sponsors are now actively investigating strategies that could make clinical trials less burdensome for patients, and interest in the decentralized clinical trial (DCT) model has grown astronomically since COVID-19, with many believing this more patient-centric approach could be the key to recruiting and retaining more patients.

According to GlobalData’s Clinical Trials database, there are currently 3,356 clinical trials involving elements of decentralization ongoing in November 2023, the majority of which (76%) are recruiting. In addition, a further 785 DCTs have been planned for the future. But what does patient centricity really mean in decentralized clinical trials, and does it have real potential to keep patients better engaged?

Ellen Weiss, VP, In-Home Solutions, Decentralized Clinical Trials at PCM Trials, believes it involves taking the trial to wherever patients are and accommodating them in their daily lives. Options include mobile nurse visits, telemedicine, and remote patient monitoring, but studies don’t have to be completely remote to make a significant improvement to the patient experience.

For example, Weiss notes it is often important for oncology patients to be dosed at the clinic, therefore trials involving chemotherapies, for instance, are not suitable candidates for full decentralization. However, with the drug infusion itself sometimes taking up to six hours at the site, there may be no reason why the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PKPD) sample – which is usually drawn another eight, ten, or twelve hours post-infusion – can’t be facilitated by a mobile nurse from the comfort of the patient’s home.

Mobile visits and patient engagement

In indications where a fully remote trial is conceivable, the in-person interactions between mobile research nurse and patient can be pivotal in keeping patients engaged with the protocol, which might otherwise rely heavily on technology for monitoring and assessing subjects.

“We often find that our nurses are really the superglue to keep that patient engaged and compliant,” Weiss says. “Not only with the dosing and the PKPD sampling regimen, which is what we’re there to do, but often our nurses are also tasked with delivering questionnaires on behalf of the CRO/sponsor or coaching patients to pick up their ePRO (electronic patient reported outcomes) device.”

It seems this more patient-friendly way of doing trials may be making a difference. According to GlobalData, dropout rates for Phase II and III trials that utilized mobile research nurse visits are around 50% less than those for a group of comparable trials without mobile research nurses (see below). The two groups of studies were matched by therapy area, region/country, and modality (small molecule, antibody, vaccine, and peptide).

Succeeding with patient centricity

When it comes to mobile nurse visits, one key point for PCM Trials is that visits don’t always have to happen in the patient’s household. “We often refer to it as a home visit and in fact, 90% of the visits we perform do happen in the home, but I think it’s that other 10% that tells a more complete story of mobile research visits,” Weiss says, listing typical alternatives such as a hotel near the patient’s workplace or the nurse’s room at their school. PCM Trials nurses have provided treatments in some far less conventional locations, too – it all depends on whatever is most convenient for the patient.

“If you need to collect multiple biomarkers from a whole family, you go where they gather,” says Weiss. “It’s going to be at Christmas dinner, or in one case it was a family reunion camp in a national park in Alaska. We had nurses in an RV with generators and multiple centrifuges and coolers with dry ice.”

Ultimately, Weiss says, the key to success is when sponsors approach the mobile visits idea early, thereby ingraining it in the entire process. Putting the patient front and center from the very beginning can have wide-reaching benefits for all stakeholders, ultimately resulting in less dropouts, less delays, and less missing data.